When asking any survey question it’s important that the person answering understands exactly what’s being asked and what responses are being sought. After all, accurate survey results stem from clear and concise questions.

Free eBook: How to increase response rates for your surveys

Ambiguous questions are the bane of all research — they leave respondents confused and lead to answers that don’t reflect what they think. As such, it’s not only important to keep your questions simple, but also to focus on one issue at a time.

As soon as you start to ask about more than one topic per question, you run the risk of confusing respondents and skewing your answers. These types of questions are known as double-barreled questions or compound questions.

For example, asking respondents how often and how much time they spend at the gym is a double-barreled question. Some respondents might go to the gym often, but not spend a lot of time there. On the other hand, others might not go frequently but spend a lot of time there. The issue is, they can only answer one of the questions.

This considered, it’s far better to ask these questions separately. It makes it easier for respondents to answer (and answer accurately) and for researchers to collate the results.

Ultimately, double-barreled questions can reduce the accuracy and reliability of your survey, potentially leaving you with unusable data.

Luckily, we’ve got you covered. In this guide, we’ll look at the main issues with double-barreled questions and how you can avoid them.

What is a double-barreled question?

A double-barreled question — otherwise known as a double direct question or compound question — is a question that essentially includes more than one topic and is asking about two different issues, while only allowing a single answer.

For example: “How much do you enjoy collecting and analyzing data?”

When it comes to survey question problems, double-barreled questions are the most common issue that comes up.

They’re a problem because the answers given can be easily misinterpreted and there’s no way for the respondent to indicate which part of the question they’ve answered. Maybe they like collecting data but hate analyzing it, or maybe they hate collecting data but love analyzing it. You’ll never know!

Fortunately, it’s simple to identify a double-barreled question. Just look for questions that ask more than one thing in the same sentence. Typically, double-barreled questions will include the conjunction ‘and’.

Let’s look at a few examples.

Examples of double-barreled questions

As we’ve mentioned, a double-barreled question is a single question that’s actually asking about two attributes.

Here are a couple of examples:

1. How would you rate our products and level of service?

As you can see from this example, two questions are being asked here: one about products and the other about the level of service.

However, a combined question like this means respondents can only provide one answer.

They might rate your products highly, but think your level of service needs improvement — or they might find your products need improvement, but rate your level of service.

The issue is that you’ll have no way of knowing which attribute they’re rating in their response.

2. How would you rate your work environment and pay?

Again, this is asking separate questions while only providing room for a single answer.

One question is asking employees to rate their work environment, the other is asking about their pay, so there’s no way to provide a clear answer.

An employee might be happy with the work environment but be unhappy with their pay, or the other way around, but there’s no way of determining which topic they’re responding to so these questions should be asked separately.

By separating these questions, you can also go into more detail later on. For example, let’s say an employee is unhappy about the work environment — in a subsequent survey (or section within your current survey), you can try to identify what elements of the work environment are making them unhappy and how to improve them.

3. How often and for how long do you visit the gym per week?

Here’s another example of separate questions combined into a double-barreled question.

In this question, respondents are asked how often they visit the gym per week and how long they spend there per visit.

There is no particular answer you can give to this question that will provide an answer to both issues, so there’s no way of obtaining accurate results.

As you can see, double-barreled questions create a range of problems for researchers and can lead to unusable data or leaders making unwise business decisions based on incorrect information.

How to avoid writing double-barreled questions

Double-barreled questions are the most common mistake in surveys, but they’re relatively easy to avoid. Here’s how:

Read your questions carefully

This sounds obvious, but make sure to thoroughly read through all your questions and look for any instances where you’re asking more than one thing.

If any question has two or more elements, but the respondent can only give one answer, you should rethink it or break it down into two or more questions.

If you can, ask a third party who hasn’t been involved in the writing of the questions to review your survey to see if they can answer questions truthfully and complete it without confusion.

Run a trial of your survey

Before putting your survey live to your full sample, send it out to a few people first and review the results to ensure they make sense based on the questions you’ve asked.

If you find yourself questioning what the respondent has responded to, you should review your questions.

Other common survey question errors

Double-barreled questions aren’t the only type of question you should avoid when it comes to getting accurate and representative survey results. Leading questions, ambiguous questions, biased questions, and so on, are all examples of common survey question approaches to avoid.

Let’s break some of them down.

Leading questions

A leading question is one in which the phrasing of the questions aims to push the respondent to answer in a certain way.

Leading questions can leave you with answers that don’t represent your sample’s opinions and wrongly confirm your own bias.

Leading questions can often read like a regular question, but contains biased language to try and push towards a particular response.

For example:

“Did you enjoy your stay at our luxury resort?”

Confusing questions

Confusing questions aren’t those which are intentionally trying to mislead respondents, but are written in an illogical way or are poorly worded.

Confusing your survey respondents can leave them guessing when completing your survey and leave you with unusable results.

For example:

“Was our customer service not unhelpful or did they resolve your problem?”

Negative questions

Negative questions are a type of question for which a “no” response indicates a positive answer, while a “yes” response indicates a negative answer. These questions are often tricky and can put off respondents. Best to avoid them if you can.

Absolute questions

These questions limit respondents’ options to 2 extreme variables, putting survey respondents in a box. These questions are typically yes or no questions.

Ambiguous questions

An ambiguous question is one in which the topic a question asks about is too broad to provide a useful answer to you, and isn’t specific enough to a particular topic.

These types of questions are often open to interpretation and can cause the responder to take a guess at what the response should be.

Any response to this type of question is unlikely to be accurate.

For example:

“If a man plays his father at tennis and he’s a professional, will he win?” — it’s not clear here who the professional is so there’s no way to know how to answer this.

Assumptive questions

An assumptive question is one in which the question assumes the person answering has prior knowledge or experience of the topic being asked about.

Assumptive questions can be used in some circumstances, such as when you’re asking a specific sample (who are experts in the field of your research), but for the most part, assumptive questions should be avoided.

For example:

“What’s your favorite HR software?” Unless your sample are well-versed in HR software (or are HR professionals), there’s a high likelihood of them not being able to answer.

Why you need to avoid double-barreled questions

Leading questions, compound questions, negative questions, assumptive questions, and double-barreled questions can result in inaccurate data — leading to organizations making decisions based on incorrect assumptions.

So to get accurate results, you need to ask clear questions. With this considered, ensuring you follow a logical path (e.g. your questions are consistent and make sense) and provide simple answer options is the best way to go.

Furthermore, by carefully examining your survey questions before putting them to your sample, you can ensure reliable results, access quality data and uncover opportunities for you to improve your products, services and brand. It’s that simple.

Avoiding double-barreled questions and developing accurate surveys with Qualtrics

A carefully designed survey needs to do three things: 1) engage respondents, 2) motivate them to complete your survey and 3) deliver valuable feedback that can guide business decisions.

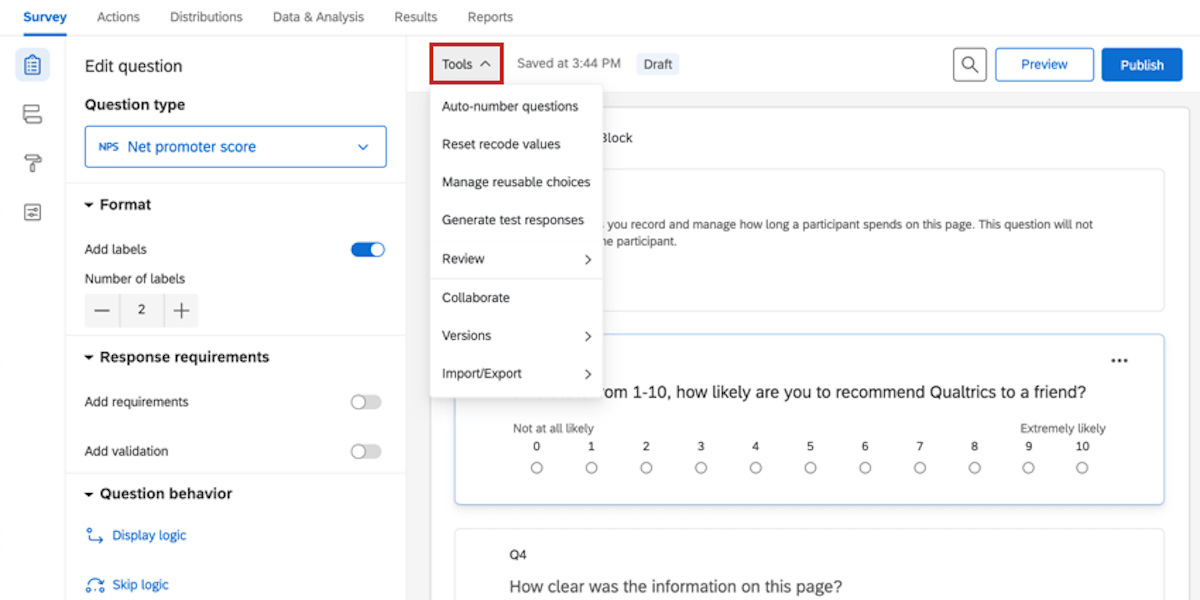

With Qualtrics, you can create reliable surveys that avoid common pitfalls and ensure you get accurate, actionable data.

Designed to streamline survey design and automate actions based on insights, Qualtrics CoreXM empowers everyone in your organization to run research projects, analyze the insights and devise a way forward.

Our software can take you through the full process and help you set your survey goals, write and design a survey that will help you meet those goals and also help you to analyze your results to gain actionable insights for better decision making.

Free eBook: How to increase response rates for your surveys